Where Lake Superior’s restless waves meet ancient Canadian Shield cliffs, red ochre images cling to stone — fading yet not forgotten. They are reminders of those who travelled these waters long before us, the Ojibwa painters who recorded visions, journeys, and spirits in the rock face now known as Agawa Rock.

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something from one of our affiliates, we receive a small commission at no extra charge to you. Thanks for helping to keep our blog up and running!

Table of Contents

Where Water, Rock, and Spirit Meet

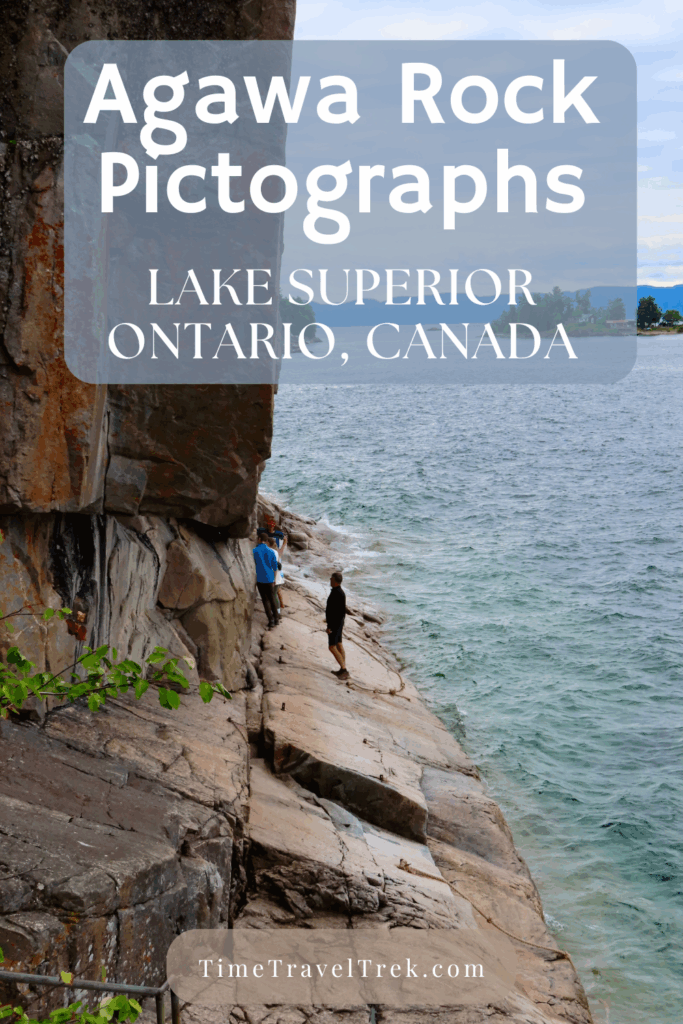

You hear it before you see it — the steady huff of the lake rolling against the cliffs of Lake Superior Provincial Park, about two hours north of Sault Ste. Marie. From the trailhead at Sinclair Cove, a short, steep path winds through mossy forest and granite outcrops. The air smells of approaching fall. As the descent steepens, the sound of waves grows louder, and suddenly, you’re standing where water laps at the stone, a metal chain your only anchor.

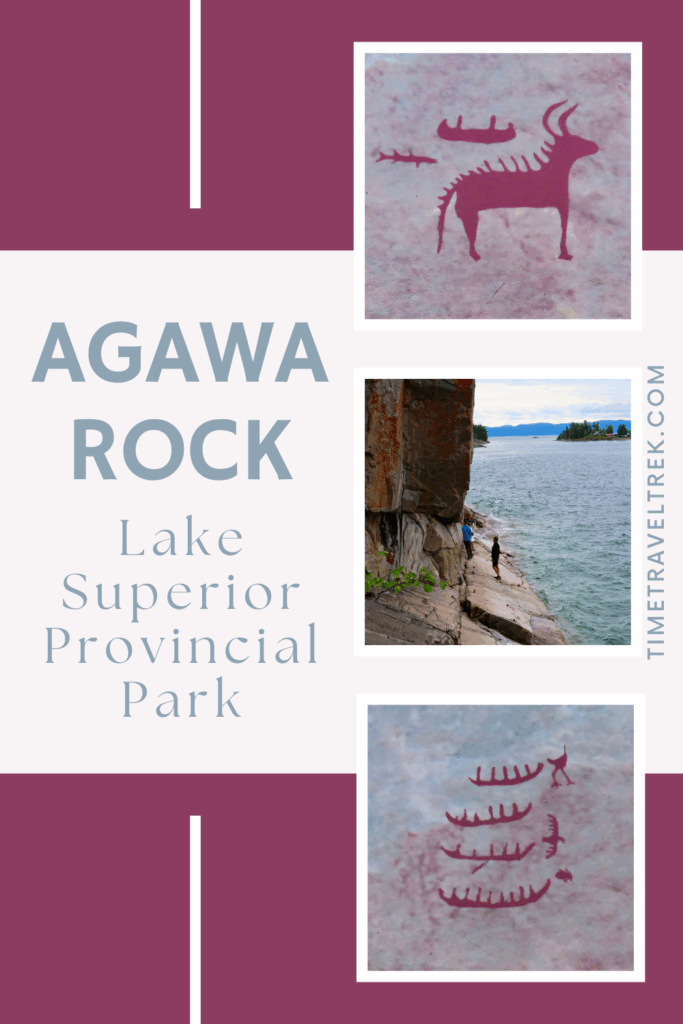

Here, on a sloping ledge just above the waterline, red pictographs emerge from the rock — faint at first, then unmistakable. Serpents coil beside moose; suns radiate energy; and canoes glide across the stone’s face. The setting feels both raw and reverent, as if you’ve stepped into a dialogue between earth and spirit – punctuated abruptly by the present and a steady flow of tourists snapping photos and moving like a tidal wave of humanity trying desperately to connect with the past.

The Agawa pictographs are among the most famous Indigenous rock paintings in Canada — a sacred site for the Ojibwa people – aka Ojibwe and Ojibway – whose ancestors paddled and prayed here. Painted with hematite mixed with fish oil or animal fat, the images have survived centuries of Superior’s storms and ice, preserved by the same elements that threaten them.

Echoes of the Ancestors

For generations, the Ojibwa have travelled this wild stretch of Superior’s shore, guided by winds, stars, and the teachings of their elders. The pictographs are not decoration but communication — records of visions received during fasting or ceremony, messages for those who would follow.

Among them looms Mishipeshu, the Great Lynx, guardian of the deep waters and keeper of storms. He is the spirit power who can summon waves, control lightning, and demand respect from those who dare to cross. Painted here in red, his image marks this as a place of power.

The first written mention of Agawa Rock came from 19th-century ethnographer Henry Schoolcraft, who learned from Chief Shingwauk that the paintings told of a warrior named Myeengun who led a fleet of canoes across Superior with Mishipeshu’s blessing. Later, anthropologist Thor Conway documented over 100 figures, noting that each was placed deliberately where spiritual energy was felt strongest.

Some images may be 400 years old; others perhaps older still. The artists never signed their names. Their legacy lies in the ochre itself — the mineral that turns the earth red when blood or fire touches it, the colour of endurance.

Walking the Trail

The trail to the pictographs is short — only 400 metres (1300 ft) — but steep, twisting through boreal forest before dropping sharply toward the lake. It passes through a narrow chasm of pinkish granite of the Canadian Shield. You won’t be alone – this is a popular stop. And even though the trail is short, you’ll have to work for your reward.

Roots curl across the path; slick rock steps descend to the water’s edge. A sign warns that conditions can be hazardous when waves are high, and it’s not hard to see why. Even on a calm day, Superior breathes with quiet but steady life force.

As you edge along the narrow ledge, chain in hand, every sense sharpens — the chill of spray, the smell of wet stone, the distant thunder of waves. Time responds to the rhythm of the lake.

Canoes on Stone, Stories in Spirit

It’s the canoes that draw me in. Simple red outlines, some filled with stick-figure paddlers, others ghosted by age. It’s no wonder one of these ancient canoe images was chosen as the logo for the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough. Each image tells of movement — across water, between worlds, through time itself. These are the oldest travel stories on the continent, recorded not on paper but in pigment and faith.

Standing here, it’s impossible not to feel the link between past and present paddlers. The same lake that challenged the voyageurs and the Ojibwa still tests today’s canoeists. The same winds that pushed birchbark canoes now ripple against Kevlar hulls. I wish we had time to put our boat in the water here.

But while the equipment has changed, the essence endures: the humility that comes from travelling by water, the awareness that every journey is shaped by forces beyond control.

Agawa Rock reminds us that canoeing in Ontario is more than recreation. It’s heritage. The canoe is a vessel of both body and spirit — a connection to the land, its stories, and the people who first navigated its pathways of stone and water.

Know Before You Go

- Location: Agawa Rock Pictographs, Lake Superior Provincial Park, Ontario — 140 km (87 mi) north of Sault Ste. Marie on Hwy 17.

- Trail: 800 m (0.5 mi) return, steep and slippery when wet. Use caution near the water.

- Respect: This is a sacred Ojibwa site. Please do not touch or photograph the paintings.

The Canoe Connection

From Quetico’s quiet lakes to Lake Superior’s sacred shores, Ontario’s waterways tell a story older than the nation itself — one that still flows, painted in red across the stone.

Pin this post for future reference!

Leave a Reply